Cities for People or Cities for Cars?

an investigation into how the private motor vehicle has changed our lives and our cities

By Hannah Brookes

INTRODUCTION

Movement, location, and transportation have always played a central role in human activities, and so the method by which we travel will always have a hand in shaping our cities and lives. Transport systems and cities are completely intertwined and interdependent, and you cannot have a truly sustainable city without a sustainable transport system.

The invention of the private motor vehicle has completely redefined our cities, and the way we inhabit them. Never before have we experienced so much freedom and mobility, yet it is debatable whether our lives and cities have actually improved. The growth in use of the personal car has brought many benefits, but we must not overlook or underestimate the negative impacts it has also had. Not only has our dependence on automobiles made cities more congested, polluted, and dispersed, but it has also made us lonelier, unhealthier, and unhappier.

We must face the fact that our cities are no longer designed for people, but for cars. This post will examine how this has happened, how automobile dependency has changed our cities and lives, and how we can move back to cities that are designed for people, for a more sustainable, free, fair, and happy future.

FROM THEN TO NOW

How Did We Get Here?

In the early twentieth century after Henry Ford streamlined the mass production of automobiles, cars began to be used in cities as a convenient replacement for horse-drawn carriages. Despite being a clearly inefficient way move people in and out of dense, crowded town centres, cars quickly became the most dominant form of transportation. This was partly due to the ‘Motordom’ movement in America, and the British Road Federation’s ‘government education’ campaigns in the 1930s, which framed cars as a way to gain freedom and improve road safety. [1]

Although stemming from a need for flexibility and mobility, cars became a statement of status and wealth. It was accepted that the automobile was the most elite of all methods of transportation due to its comfort, convenience, speed, and social status, and that the only reason for not owning one was because you could not afford to. This attitude, and the increasing construction of infrastructure catering only to cars, ensured the future of the automobile as the primary form of transportation in the developed and now the developing world. Indeed, we have become automobile dependant.

Once our reliance on automobiles had begun, the rise of car use and the decline of public transport became self-perpetuating. As cars became the most desirable way to travel, more investment was given to developing roads for cars, and was taken away from developing good public transportation systems. By the 1950s the America government was spending 75% of its transportation funding on building and repairing roads for cars, and less than 1% on public transport. [2] This made it even harder to avoid having a car as public transport was unreliable and sometimes unavailable. More roads were built to try and combat the now rising tide of traffic, however, more road space just encouraged greater car use, and congestion became even worse.

European cities have evolved over thousands of years, resulting in a dense, human scale urban grain not designed for the type and volume of traffic that the 20th century brought. Increasing road space within city centres in most cases was problematic, so planners turned instead to ring roads, eating into green belts and drawing amenities to the outskirts of towns. This diminished the soul and life of city centres.

Whilst the advantages of car use are clear in rural settings, these benefits diminish rapidly in urban environments. The over reliance on cars in cities has led to congestion, the depletion of public transportation, and less freedom and choice in the way that we travel. Additionally, the increased dominance of cars in city streets, and the reconfiguration of urban systems to accommodate drivers makes people feel less safe using alternate forms of travel such as cycling or walking, further increasing the dependence on the automobile.

FROM INTERTWINED TO DIVIDED

How Cars Have Divided Us Physically, Socially and Emotionally

The automobile promised to make everything accessible, but has actually distanced us from each other and the world around us. The dispersing of people and spread of suburbs has now led us to a situation where we live far away from everything, increasing our reliance on personal cars and making it more difficult to keep in contact with our families and friends. This is especially the case for children and the elderly, who may not have the ability to drive, nor the accessibility of good public transport, or the option to safely cycle or walk. This can lead to isolation, loneliness, inaccessibility of services, and essentially a loss of the freedom that the car was supposed to provide.

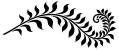

Up until the 1900s the streets were for everyone. There were no traffic lights, lanes, codes, or crossings, and people were free to move as they please. This was relatively safe as even the fastest vehicles were not that fast, and so the street could be used by everyone, as a market, throughfare, playground, and park. It was messy, but it was free. [3] Since the introduction and mass use of the automobile, our roads and streets have become increasingly segregated. Cars, bikes, and people must stick to their lane, and follow the rules. The streets are no longer a free place. Additionally, by pushing pedestrians to traffic islands, separated pavements and overhead walkways in the name of safety, we have further emboldened drivers and discouraged walking and cycling.

When travelling through a landscape in a car, you are not really experiencing it. The threshold between yourself and the rest of the world has been extended from your body to the outside of the car, shutting out smells, sounds, weather, and social interaction. Not only this, but the speed at which you move in a car allows you to glide past beautiful places and moments without even noticing them pass by. The world stops being something you are immersed in and becomes just a blurry image speeding past in your periphery. The joy of appreciating your surroundings, breathing in fresh air, and feeling in touch with nature is lost, you are completely disengaged with the world around you. Your view of the world has become myopic.

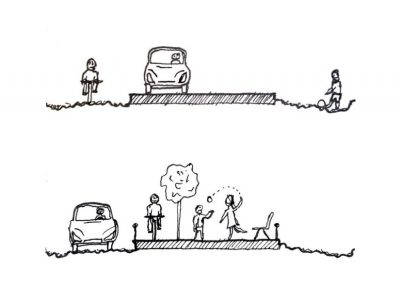

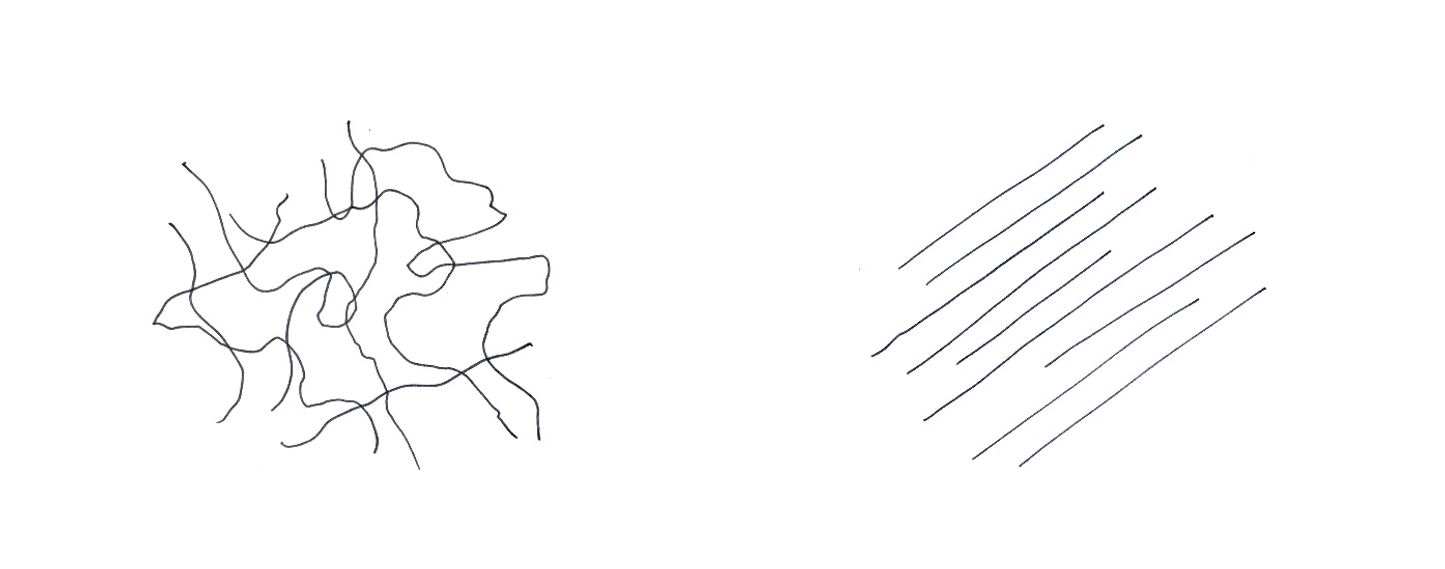

Not only does car travel remove your interaction with your environment, it also removes interaction with other people. By their very nature, roads are linear and processional. Everyone is moving in the same direction, at the same speed, like beads on a string. As a result, there is no interaction between people, as opposed to the messy, interconnected, overlapping patterns that people naturally move in, like Brownian motion. By travelling in this linear way, we are eliminating the serendipity of chance encounters, bumping into friends, or making small talk with strangers; small interactions that have a significant impact on our wellbeing and our feelings of contentment and connection to others. These experiences should be what city life is all about, but by travelling in cars we are denying ourselves these simple pleasures. [4]

Cars separate us from other people physically, and also create a clear class division between those who can afford cars, and those who cannot. Those who cannot are at a further disadvantage because of the lack of investment in public transport. Adults without cars are continuously finding it harder to shop, get medical services, or get to work, and in the UK one in four young people report missing a job interview because it was just too difficult to get there, further increasing inequalities. [5] This is even more apparent in developing countries where only the most affluent have cars, yet cars are the most prioritised vehicles in the streets.

FROM PLACES TO SPACES

How Choosing Movement Over Dwelling Has Changed Our Experience of Places

A place is somewhere you inhabit, and a space is somewhere you move through. By choosing movement over dwelling, we have downgraded the public realm from place, to space. This has resulted in dead, soulless cities, with more cars than people occupying the streets. We have sacrificed the quality and experience of public spaces, for the convenience of those who wish to pass through them as quickly as possible.

Journey Without Cars

Your path may contain many moments of pause; you wait at a bus stop, you bump into a friend, you rest on a bench, you buy a coffee. You are really experiencing the journey and connecting with the places that you pass through.

Journey In a Car

You move straight from your start point to your pre-determined destination. There is no need to stop or detour unless you get stuck in traffic – how frustrating! You only experience the spaces you pass through as a quick glance through a window.

‘You cannot separate the social life of urban spaces from the velocity of the activities happening there. Public life begins when we slow down.’ [6]

The lack of interaction with our environment when driving in a car prevents what Jan Gehl calls ‘optional activities’ and ‘social activities’, the small interactions with your environment and the people around you that make up what city life should be all about. When you drive instead of walking somewhere, you are removing the opportunity to have these little unplanned interactions. [7]

The thing that interests us the most, and that we find most entertaining, is other people. To have a thriving, lively urban space, it needs to be inhabited. That is what will encourage people to stop, linger, look, and dwell in a public place. But we do not want to dwell in a place completely dominated by cars and movement, and so we are left with cities all over the world more populated by cars than by people.

‘The city’s greatest attraction is other people’ [8]

We are simply not evolved to live in a world with objects moving as fast as cars do, and the psychological impact of occupying the same space as vehicles is substantial. The human body can withstand impact with hard surfaces up to 20mph, but any faster than that would probably be fatal. So being surrounded with fast moving, large vehicles, that also happen to be noisy and smelly, is inevitably going to make us feel somewhat uncomfortable and anxious. This is clearly not a desirable condition, yet this is what we experience on almost all city streets. This negatively impacts our experience and opinion of a city’s public realm and makes us feel exhausted and stressed after a day in the city. [9]

FROM PUBLIC SQUARE TO CAR PARK

How Cars Have Shaped the Physical Form of Spaces

Good public space and a good public transport system are simply two sides of the same coin’ [10]

Not only has the automobile impacted on the way we live our lives, but it has also reshaped the physical form of our buildings, streets, and cities.

Shops lining high streets no longer aim to draw in pedestrians, but to catch the fleeting attention of someone driving past. Market stalls and posters have been replaced by huge eye-catching signs and expansive horizontal glass walls, displaying the contents of each shop for as long as possible for drivers. Pavements have shrunk whilst roads have expanded.

The impact of the automobile can be seen in the addition of multistorey car parks and large expanses of tarmac in city centres, and the gradual loss of the traditional market place. It can be seen in the lack of attention to public spaces and parks, and the miles of driveway in front of every house.

Once you start looking, the physical evidence of our dependence on the automobile can be seen everywhere, in towns and cities all over the world.

FROM NOW TO THE FUTURE

How Can We Move Forwards?

COPENHAGEN

‘We found that if you make more road space, you get more cars. If you make more bike lanes, you get more bikes. If you make more space for people, you get more people, and of course then you get public life’. [11]

In terms of its transportation system, Copenhagen is one of the most successful cities in the world. One of the first cities to turn its back on the automobile and invest in alternative forms of transport, 62% of its residents now cycle to work or school, and it has a reputation as one of the happiest cities in the world. [12]

Copenhagen’s traditional main street was converted into a pedestrian promenade in 1962. This was part of a large-scale project in the early 1960s that aimed to reduce car traffic and parking in the city centre, increase pedestrian traffic, to create better and safer conditions for bicycles, and better spaces for city life. Prioritising space for bikes, making cycling and walking safer, and gradually reducing space for vehicular travel, has made cycling the fastest, safest, cheapest, and most enjoyable way to travel here, and Copenhagen now has five times as many bikes as cars. By inviting the residents of Copenhagen to walk, stand and inhabit their city, they have achieved new urban life and a bustling, active atmosphere. [13]

BOGOTÁ

‘We think its totally normal in developing-country cities that we spend billions of dollars building elevated highways while people don’t have schools, they don’t have sewers, they don’t have parks. And we think this is progress, and we show this with great pride, these elevated highways!’ [14]

Bogotá at the end of the 20th century was in a dire state; impoverished, polluted and with a reputation for assassinations and crime. When Enrique Peñalosa was elected as mayor in 1997, he set about improving the transportation system and public spaces in the city, with the goal of improving the happiness of the people of Bogotá. The city had gradually been reorganised around private automobiles, despite only one fifth of families owning a car, and most public and green spaces were private. [15] There were no cycle or footpaths, and the public transport system had been nicknamed the ‘war of the centavo’ due to private bus companies racing each other to often unofficial stops to compete for passengers, causing severe congestion and chaos on the roads. [16]

‘A city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can’t be both.’ [17]

Peñalosa firstly tackled public transport, introducing the Transmilenio bus system. By giving the best road space to busses, he raised the status of public transport and of the people who used it making it a more desirable way to travel. He also abolished plans to build a new highway expansion and instead poured his budget into hundreds of miles of new cycle lanes, parks, and footpaths. [18]

Bogotá also has a famous weekly Ciclovia (‘cycle path’), where the main streets of Bogotá are blocked off for cars and instead open for thousands of cyclists, letting them claim back the streets. This event is hugely popular with Bogotáns, with one-and-a-half million citizens participating each week. [19]

THE FUTURE POTENTIAL

Copenhagen and Bogotá prove that cities are hugely adaptable. By prioritising other modes of transportation, we can reduce the dominance of automobiles, and create a future where all urban areas have multiple options of travel. In other words, we could create a future where transport is about freedom and connectivity, not dependence.

CONCLUSION

In the end, cities are about people. By designing for cars, we have forgotten who the city is for, and created cities that feel dead, polluted, and unsafe. The invention of the personal car promised us freedom, but it has not delivered. By taking space and resources away from other modes of transportation, it has instead limited us all to only one primary way of moving, with the additional cost of the loss of lively, unpolluted, safe cities, and happy, healthy citizens.

We can see from Bogotá and Copenhagen that there are solutions to this problem. Many of those solutions do not even require much funding, just a shift in attitude and behaviour. We do not necessarily need to remove cars from our cities completely, but by increasing the status, quality, and availability of other forms of transportation, we could remove our reliance on automobiles, and gain freedom of choice in the way we move.

By creating systems where people are free to use whichever form of transportation works for them, in cities where people are encouraged to inhabit spaces instead of passing through them, we will create active, safe, efficient, happy, and sustainable cities. In essence, we need to start designing our cities for people again, and not for cars.

FOOTNOTES

- Charles Montgomery, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 71-76.

John Fuller, ‘Why Did Cars Become the Dominant Form of Transportation in the United States?’, How Stuff Works, 2008, accessed 16 December 2020, https://auto.howstuffworks.com/cars-dominant-form-transportation.htm

- Montgomery, 2013, 70.

Jonathan Barnett, ‘Life Takes Place on Foot’, Planning 80(2014), 32.

- Montgomery, 2013, 249.

- Montgomery, 2013, 173-174.

- Barnett, 2014, 32.

- Jan Gehl, Cities for People (Washington: Island Press, 2010), 25.

- Montgomery, 2013, 172-174.

- Gehl, 2010, 7.

- Gehl, 2010, 19.

- Erik Kirschubaum, ‘Copenhagen Has Taken Bicycle Commuting to a Whole New Level’ Los Angeles Times, 2019, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2019-08-07/copenhagen-has-taken-bicycle-commuting-to-a-new-level

- Gehl, 2010, 11.

- Montgomery, 2013, 241.

- Montgomery, 2013, 4-5.

- Smart Cities Dive, ‘Bogotá, Colombia’s Tranmilenio: How Public Transportation Can Socially Include and Socially Exclude’, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/bogota-colombias-tranmilenio-how-public-transportation-can-socially-include-and-exclud/95236/

- Montgomery, 2013, 5.

- Montgomery, 2013, 241.

- Alma Guillermoprieto, ‘This city bans cars every Sunday – and people love it’, National Geographic, 2019, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/2019/03/city-bans-cars-every-sunday-and-people-love-it

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Colville-Andersen, Mikael, Copenhagenize: The Definitive Guide to Global Bicycle Urbanism (USA, Island Press, 2018)

Gehl, Jan, Cities for People (Washington: Island Press, 2010)

Jacobs, Jane, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Modern Library, 1993)

Kenworthy, Jeffrey, and Newman, Peter, The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities are Moving Beyond Car Based Planning (Washington: Library Press, 2015)

Mees, Paul, Transport for Suburbia: Beyond the Automobile Age (Earthscan, 2009)

Montgomery, Charles, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (London: Penguin Books, 2013)

Barnett, Jonathan, ‘Life Takes Place on Foot’, Planning 80(2014), 31-33

Bruns, André, and Matthes, Gesa, ‘Moving into and within Cities – Interactions of Residential Change and the Travel Behaviour and Implications for Integrated Land Use and Transport Planning Strategies’, Travel Behaviour and Society 17(2019), 46-61

Kenworthy, Jeffrey, and Laube, Felix, ‘Automobile Dependence in Cities: An International Comparison of Urban Transport and Land Use Patterns with Implications for Sustainability’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 16(1996), 279-308

Kenworthy, Jeffrey, ‘Is Automobile Dependence in Emerging Cities and Irresistible Force? Perspectives from São Paulo, Taipei, Prague, Mumbai, Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou’, MDPI: Sustainability 9(2017)

Lave, Charles, ‘Cars and Demographics’, ACCESS Magazine 1(1992), 4-10

Perrone, Camilla, ‘’Downtown Is for People’: The Street-Level Approach in Jane Jacobs’ Legacy and its Resonance in the Planning Debate Within the Complexity Theory of Cities’, Cities 91(2019), 10-16

Schubert, Dirk, ‘Jane Jacobs, Cities, Urban Planning, Ethics and Value Systems’, Cities 91(2019), 4-9

Bartels, Meghan, ‘Meet the Author: Q&A With… Jan Gehl!’, Island Press, 2014, accessed 16 December 2020, https://islandpress.org/blog/meet-author-q-jan-gehl

Bayley, Stephen, ‘How Cars Changed the World’, Goodwood, 2019, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.goodwood.com/goodwood-estate/estate-news/how-cars-changed-the-world/

BBC News, ‘Birmingham Cars Could be Banned from Driving Through City Centre’, 2020, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-birmingham-51088499

Drive Safely, ‘Evolution of the Automobile’, 2020, accessed 16 December 2020, https://www.idrivesafely.com/defensive-driving/trending/evolution-automobile

Fuller, John, ‘Why Did Cars Become the Dominant Form of Transportation in the United States?’, How Stuff Works, 2008, accessed 16 December 2020, https://auto.howstuffworks.com/cars-dominant-form-transportation.htm

Guillermoprieto, Alma, ‘This city bans cars every Sunday – and people love it’, National Geographic, 2019, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/2019/03/city-bans-cars-every-sunday-and-people-love-it

Hidalgo, Darío, ‘Urbanism Hall of Fame: Jan Gehl Integrates Humanity into Urban Design’, The City Fix, 2014, accessed á17 December 2020, https://thecityfix.com/blog/urbanism-hall-fame-jan-gehl-integrates-humanity-urban-design-copenhangen-cities-for-people-dario-hidalgo/

Jaffe, Eric, ‘How to Design a Happier City’, Bloomberg City Lab, 2013, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-12-09/how-to-design-a-happier-city

Kirschubaum, Erik, ‘Copenhagen Has Taken Bicycle Commuting to a Whole New Level’, Los Angeles Times, 2019, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2019-08-07/copenhagen-has-taken-bicycle-commuting-to-a-new-level

Melosi, Martin, ‘The Automobile Shapes the City’, Automobile in American Life and Society, 2010, accessed 17 December 2020, http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Environment/E_Casestudy/E_casestudy2.htm

Mobility and Transport, ‘The Importance of the Private Car’, The European Commission, 2020, accessed 17 December 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/specialist/knowledge/old/safety_versus_mobility_and_quality_of_life/the_importance_of_the_private_car_en

Moss, Stephen, ‘End of the Car Age: How Cities are Outgrowing the Automobile’, The Guardian, 2015, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/apr/28/end-of-the-car-age-how-cities-outgrew-the-automobile

Sharing Cities Alliance, ‘The City of Copenhagen’s Bicycle Strategy’, 2017, accessed 17 December 2020, https://sharingcitiesalliance.knowledgeowl.com/help/copenhagen

Smart Cities Dive, ‘Bogotá, Colombia’s Tranmilenio: How Public Transportation Can Socially Include and Socially Exclude’, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/bogota-colombias-tranmilenio-how-public-transportation-can-socially-include-and-exclud/95236/

Smart Cities Dive, ‘Urbanism Hall of Fame: Enrique Peñalosa Leads Bogotá’s Inclusive Urban Transformation’, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/urbanism-hall-fame-enrique-pe-alosa-leads-bogot-s-inclusive-urban-transformation/1030186/

Sumantran, Venkat, Fine, Charles, and Gonsalvez, David, ‘Our Cities Need Fewer Cars, Not Cleaner Cars’, The Guardian, 2017, accessed 16 December 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/oct/16/our-cities-need-fewer-cars-not-cleaner-cars-electric-green-transport

Visit Colombia, ‘Bogota: Bike Friendly City’, accessed 17 December 2020, https://www.colombia.co/en/colombia-travel/tourism-by-regions/bogota-bike-friendly-city/